Style Transfer for Text - Advances and Challenges

05 Nov 2019Introduction

‘Neural Style transfer is a FRAUD, and a very expensive, hoax! The task is a complete and total disaster’!

It would be quite unexpected if the rest of this article continued in the style of a well-known politician from North America, and for many, it would be an arduous read. Humans are adept at modulating the style of the content we generate based on the situational context, the cultural and demographic attributes of the readers, and the intents of the author. This is a hallmark of effective communication and it would serve our automated text generators well to possess this skill. The task of generating text conditioned on such attributes is called ‘controlled text generation’. In this article, we deal with a related task called Textual Style Transfer. The aim of this task is to automatically convert text written in a source style to text written in a target or multiple target styles, while keeping the content intact.

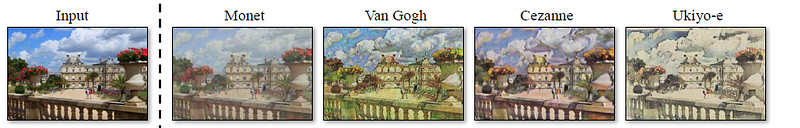

Style transfer using neural networks has seen considerable success in the computer vision domain. In this version of the task, a ‘content’ image is merged with a ‘style’ image to generate a new image that renders the content in the new style. Models based on Generative Adversarial Networks like CoupledGAN’s and CycleGAN have been extensively utilized for image style transfer, taking advantage of large amounts of non-parallel data. However, these techniques cannot be adapted easily to the textual domain due to the discrete nature of text. In this post, we will describe supervised and unsupervised techniques for textual style transfer along with their pitfalls as well as provide an insight into the state-of-the-art models that try to alleviate those pitfalls.

The above image is a demonstration of image style transfer - the input image is rendered in the style of Monet, Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Ukiyo-e.

Image credits - Zhu et al., Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks.

Applications

There are several textual style transfer problems that are being tackled by current research.

A popular one is to convert text written in an informal style to text written in a formal style. Other such examples include making text more polite, persuasive, diplomatic, or less sarcastic.

There has also been some work on using style transfer techniques to convert text to its more simplified version. An example would be converting the text of a document so that it is appropriate for younger readers or non-native speakers of a language. The same techniques have also been used in text archaification or text modernization. An example would be converting text written in Shakespearean English to Modern English.

Ultimately, style transfer for text boils down to reliably separating the content of the text from the style in which it is written. This separation of content and style can be exploited to anonymize text, rendering the author of the text safe from being outed by linguistic forensics techniques that can identify a person based on subtle linguistic cues in their writing style.

Word of caution - there seems to have been some concept creep in the literature. As you might have noted, not all of the transfer attributes mentioned above can be strictly defined as a stylistic trait. Due to this, some of the techniques proposed in the literature cannot be generalized to the diverse range of transfer tasks. Unfortunately, since considerable research literature has accumulated using this rather expansive definition of the word ‘style’, we will proceed with the same terminology.

Supervised Techniques

Textual style transfer can be seen as a machine translation task with highly overlapping source and target vocabularies. It can also be seen as a paraphrasing task where the paraphrasing is conditioned on the given attributes. Many style transfer models draw heavily from techniques used for solving these tasks.

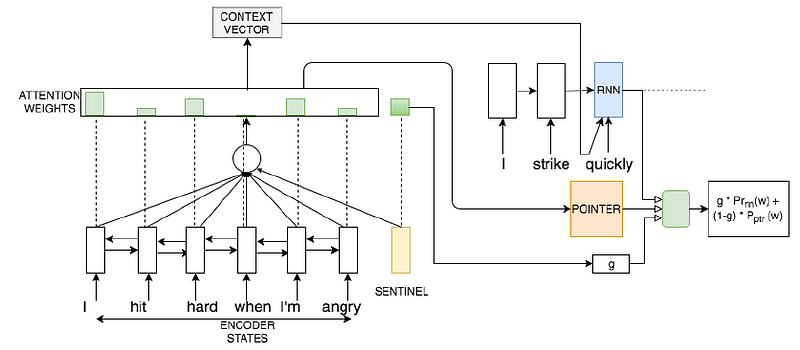

In one of the most seminal papers on supervised techniques in this field, Harsh et al.. describe a model to convert from a source style to a target style using a seq2seq model enriched by pointer networks. The overall architecture is as follows:

The source sentence is encoded using a bidirectional LSTM. The encoded representation is then passed to a decoder which is comprised of two components - an RNN module and a pointer network module. The RNN predicts the probability distribution of the next word in the output over the target style vocabulary, while the pointer network predicts the probability distribution of the next word over the input sequence. The purpose of the pointer network is to enable direct copying of words from the input sequence to the output. This is especially useful for the task since we expect the vocabulary to be largely overlapping and that a non-trivial part of the sentence remains the same. The pointer network module is also helpful in predicting rare words and proper nouns which would otherwise have a hard time being predicted using the RNN module.

The next token in the output is determined by a weighted addition of the probabilities from the RNN module and the pointer network module. The weights are based on the encoder output states and the previous decoder state. A conceptual diagram depicting this architecture is shown below:

Image Credits: Jhamtani et al., Shakespearizing Modern Language Using Copy-Enriched Sequence-to-Sequence Models

Unsupervised Techniques

The difficulty in collecting and annotating parallel data has led to research being focused on unsupervised techniques that work on unpaired source and target style datasets.

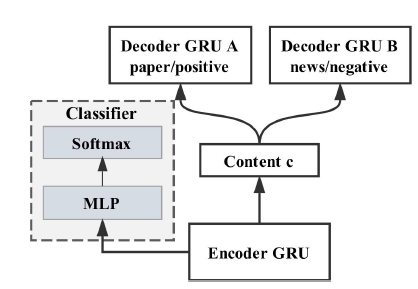

These techniques generally rely on disentangling the content and style of the text in latent space. Fu et al. propose two models that perform style transfer based on this separation. They demonstrate these models on two tasks - The Paper-News Title task which aims to re-write the title of a research paper in the form of a news article title, and the sentiment reversal task, which aims to translate a sentence from positive to negative sentiment. These models have formed the base framework for numerous subsequent research papers.

Multi-decoder model: This model uses a modified autoencoder architecture. The autoencoder in its original formulation seeks to generate a compressed representation of an input x such that the representation can be used to regenerate the original sequence.

For this task, the compressed representation is generated in a way such that it only represents the content with all stylistic attributes stripped off. Separation of content from style is performed using adversarial training.

The adversarial network is comprised of two components. One component acts as a style classifier that tries to predict the style of the input text using the encoded representation. The other component tries to set the weights of the encoder in such a way that the classifier is unable to correctly predict the style. This eventually ensures that the encoded representation contains only the content and is not discriminative of styles.

Style-specific decoders are then used to generate text in the target style, taking the content-exclusive encoded representation as input.

A conceptual diagram of this model is shown below:

Image taken from Fu et al., Style Transfer in Text: Exploration and Evaluation

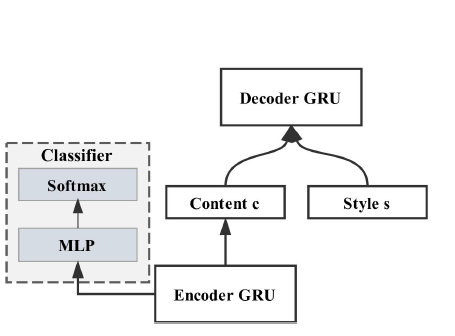

Style embedding model: Similar to the above method, this model uses a modified version of an autoencoder. In this model, each style is represented by a d-dimensional style embedding vector. The encoder and the adversarial network are the same as in the multi-decoder model. The embedding vectors for the styles are jointly trained with the network.

For the decoder model, the input is the encoded representation of the input text along with the style embedding vector representing the target style. The same decoder can be thus used to generate text in multiple styles.

Image taken from Fu et al., Style Transfer in Text: Exploration and Evaluation

Other techniques like variational autoencoders have also been extensively experimented with.

Evaluation Metrics

Textual style transfer needs to be evaluated across three dimensions:

- The coherence and fluency of the generated text.

- The degree of content preservation from the source text.

- The degree of transfer strength to the target style

Coming up with automated evaluation metrics is extremely difficult for text generation tasks, and this remains an active field of research. An evaluation metric that would do as well as humans will have to essentially solve Natural Language Understanding, which is still a pipe dream. So far the community has resorted to using metrics based on heuristics such as BLEU, PINC, and TERp.

BLEU is a well-known evaluation metric used in machine translation. BLEU offers itself as a proxy for semantic equivalence by measuring the n-gram overlap between the generated text and the gold label text, with a brevity penalty for length normalization. The hope is that a higher BLEU score indicates better content preservation.

PINC is an evaluation metric that comes from the paraphrase community. The PINC score is a measure of lexical dissimilarity that calculates the percentage of n-grams in the generated text that does not appear in the source text. Aggressive changes to the source text lead to a higher PINC score. However, the PINC score does not take into account the meaning preservation or fluency of the generated text at all.

TERp is an evaluation metric from the machine translation community that is used sometimes. It is a measure of the number of edits needed to convert the generated text to the gold truth text. The hope is that the lower the TERp score, the better the content preservation.

Transfer strength is evaluated by running a style classifier on the generated text that has been trained on data from the target style, preferably in the same domain. Other efforts to evaluate content preservation include using distance metrics between encoded representations of the generated text and the gold label text.

Pitfalls

So far, we have given an overview of techniques that are commonly used for textual style transfer. However, it is not all sunshine and hay as this task is fraught with severe challenges. In this section, we will describe some of them.

Alas, there seems to be a tradeoff between the content preservation and the transfer strength objectives. Simply copying the source sentence in its entirety will result in 100 percent content preservation and 0 percent transfer strength. In the same vein, the more aggressive the changes to the source sentence, the higher the chances of greater transfer strength but also higher the chances of losing the original meaning.

Adversarial training is hard and needs a lot of data. The text generated through this technique is of poor quality, and the content preservation-transfer strength tradeoff is extremely noticeable. In practice, separating content from text is extremely difficult, and the discriminator part of the adversarial network can be easily fooled without actually having to drop stylistic content. This has prompted researchers lately to explore other, possibly more simpler avenues. No wonder, most recent papers in this field use the phrase ‘simple but effective’ to describe their techniques.

Progress made on this task can be potentially deceptive. Different style transfer tasks have varying degrees of difficulty. The most commonly experimented tasks in current research papers are the informal-formal conversion task and the sentiment reversal task. It should be noted that these tasks are also perhaps the easiest of the style transfer tasks, as the style is represented by surface-level lexical units rather than being an abstract emergent property, thus making content and style disentanglement easier.

For example, Rao et al. show that an informal to formal sentence conversion for the most part consists of lexical changes like capitalizing the first letter of proper nouns, capitalizing the first letter of a sentence, expansion of contractions, and deletion of repetitive punctuation, all of which can be represented by a rule-based system that can provide a competitive baseline.

Similarly, with the sentiment reversal task, certain words and phrases are heavily indicative of sentiment and thus can be separated from the non-sentiment bearing words with relative ease. Li et al. introduced a Delete, Retrieve, Generate framework that exploits the heavily indicative style-bearing words and phrases for this task by using it as an inductive bias for their model. The Delete, Retrieve, Generate framework is truly simple and consists of the following sequence of steps:

- Delete - Identifies words and phrases indicative of the source style and deletes them.

- Retrieve - Identifies a sentence in the target training set that is closest to the source sentence by means of a distance measure.

- Generate - Use the attribute markers from the retrieved sentence and the source sentence with deleted phrases as input to an encoder and use the decoder to generate the sentence in the target style.

While this approach looks promising, the inductive bias used limits it to only those style transfer tasks where the stylistic attributes are encapsulated in words or phrases. This method will not work well in cases where style is a more abstract concept and the content and the style are intertwined in very subtle ways.

State-of-the-art

In the previous section, we explored various challenges that have stemmed research progress on this task. In this section, we will describe how the latest papers aim to overcome these challenges. Specifically, we will focus on style transfer related papers that will be presented at the EMNLP 2019 conference this November.

Dealing with the data bottleneck:

Underpinning all technical pitfalls is the fundamental data scarcity problem. To make up for the lack of parallel training data, techniques for automatically inducing pseudo-parallel datasets as well as leveraging large scale out-of-domain data have been devised. We will describe the state-of-the-art on each of these techniques below:

Generating pseudo-parallel datasets

Jin et al. devise an iterative algorithm to generate a pseudo-parallel dataset that aligns sentences from source and target style datasets. The iterative algorithm uses distance measures to guide the sentence alignments. Before we delve into the algorithm, let us take a quick look at the distance measures used:

Word Mover Distance: Word Mover distance is a handy distance measure introduced by Kusner et al. which makes use of word embeddings for semantic similarity. Sentences are represented in vector space using a weighted combination of word embeddings representing the words in the sentence. WMD is based on the Earth Mover distance and represents the minimum distance needed by words in sentence s1 to ‘travel’ in order to reach the representation of sentence s2.

The advantage of using WMD is that it does not require hyperparameters, as well as its high level of interpretability. The formulation of WMD accounts for sentences with unequal lengths, due to the usage of weighted embeddings where the weights sum to 1.

Semantic Cosine Similarity: ELMo embeddings of all words comprising a sentence are averaged to form a context-aware sentence representation. The semantic similarity of two sentences is then calculated by calculating the cosine of their representations.

The iterative algorithm is called IMaT (Iterative Matching and Translation) and comprises of Matching, Translation, and Refinement steps.

Consider a corpus X comprised of sentences x1,x2,…xm in the source style. Similarly, consider a corpus Y comprised of sentences y1,y2,…yn in the target style. These sentences are not aligned and m need not be equal to n.

Initialization: The pseudo-parallel corpus is initialized by pairing sentences from X and Y using distance measures. More specifically, for each sentence x1 in X, the sentence from Y that has the highest cosine semantic similarity score and exceeds a particular threshold γ is picked. Let the subset of X for which a pair exists be denoted by X~. Let the subset of Y which has been matched with the sentences in X be denoted by Yt~ where t refers to the iteration number, which is 0 for the initialization phase. The remaining part of the algorithm is run for multiple iterations.

Matching: For iteration > 0, X~ is matched with Yt~ just like in the initialization phase. In this case, Yt~ is generated in the Refinement step from the previous iteration. Let the output of the matching be denoted by tempt. Now, each sentence in X~ has two candidate alignments - one in tempt and one in Yt~. The Word Mover distance between each sentence xi and the two candidate alignments are calculated. If the candidate from tempt has a lower WMD score than the candidate from Yt~, then Yt~ is updated with the candidate from tempt.

Translation: During the translation step, a seq2seq machine translation model that uses attention is trained from scratch over the pseudo-parallel corpus (X~, Yt~). Let this model be denoted by Mt.

Refinement: Each sentence in X~ is fed as input to the machine translation model to generate a translation. Let the generated translations be denoted by tempt. Now, each sentence in X~ has two candidate alignments - one is the output of the machine translation model and one is the sentence matched during the Initialization/Matching step. The Word Mover distance between each sentence xi and the two candidate alignments are calculated and the candidate with the smaller distance is inserted into Yt+1, which is carried into the next iteration.

The Matching, Translation, and Refinement steps are repeated for several iterations to refine the pseudo-parallel corpus.

The paper contains a succinct description of the algorithm as shown in the figure below:

The authors report that this model beats the state-of-the-art on the formality and sentiment transfer tasks, with improvements in fluency, content preservation, and transfer strength. The authors show that the iterative Translation and Refinement steps progressively create a better-aligned corpus, thereby enhancing content preservation abilities.

Leveraging out-of-domain data

Can we utilize the large scale out-of-domain data to improve our results on the style transfer task? Yes, but we need to take into account the domain shift and implement measures to ensure that the generated text doesn’t exhibit spurious domain-specific characteristics. Li et al. introduce two style transfer models that provide for domain adaptation - one in the case where the style labels are known for the out-of-domain data, and one where the style labels are unknown or are not relevant to the task.

For purposes of clarity, we will henceforth refer to the out-of-domain data as the source domain and the domain that we are performing style transfer in as the target domain. As an example, for the sentiment reversal task, we may aim to transfer from negative to positive sentiment on the Yelp food reviews dataset and would like to leverage IMDB reviews that exhibit a domain shift to improve our model. In this case, the source domain is the movie reviews and the target domain is the food reviews.

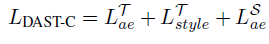

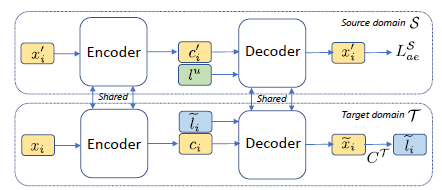

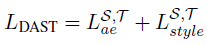

Domain adaptive style transfer using source domain data having unknown styles (DAST-C):

The model is made up of 2 components - an autoencoder to ensure content preservation, as well as a style classifier for directing generation of sentences in a particular style.

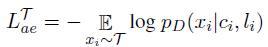

The reconstruction loss of the autoencoder can be described by the loss function:

Where,

ci refers to the compressed representation of a sentence xi when run through the Encoder.

li refers to the source style.

T refers to the target domain.

To perform style transfer, the decoder replaces li with li~.

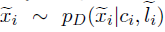

The output sentence x~i is sampled from

This formulation alone will not help in style transfer, as the decoder can simply copy the input sentence to minimize the reconstruction loss. Hence a style classifier is used to discriminate between sentences containing different styles.

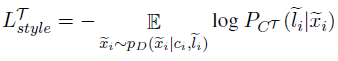

The style classifier loss can be described by the loss function:

Where CT is a style classifier that has been pre-trained on the target domain.

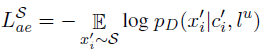

With the assumption that out-of-domain data can be used by the model to model generic content and thus enhance content-preservation, both the source domain and target domain data are used to jointly train the autoencoder. The loss function of the autoencoder with respect to the source domain alone can be described by the following objective:

Where lu refers to an unknown or irrelevant style,

S refers to the source domain.

The total loss is the sum of the autoencoder losses from the source and target domains as well as the style classifier loss.

LTstyle ensures that generated content contains target domain-specific style characteristics since the style classifier is trained on the target domain only.

Meanwhile, LaeS benefits from the massively large source domain data to ensure better modeling of content representation, thus boosting content preservation.

The architecture diagram is shown below:

Image credit: Li et al. Domain Adaptive Text Style Transfer

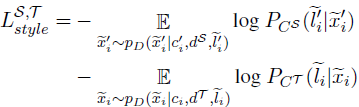

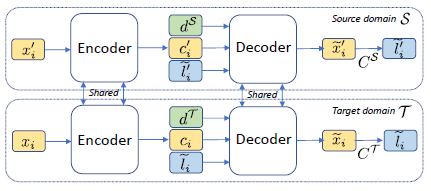

Domain adaptive style transfer with similarly styled source domain data (DAST)

In this case, the source domain data can help with both content preservation as well as style transfer, since the source domain sentences exhibit the same styles that we are concerned with in the target domain.

Care should be taken that the stylized generated sentence should not exhibit source domain characteristics. To ensure this, the model uses domain vectors, with a domain vector learned for each domain during training.

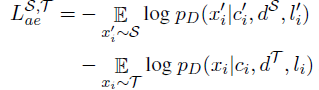

The autoencoding loss is now

where dS and dT are the source domain and target domain vectors respectively and li = li’

The domain vectors bias the decoder towards generating sentences with domain-specific characteristics. This idea is also extended to the style classifiers, thus resulting in style-specific classifiers being learned.

Where CS and CT are style classifiers learned separately on the source and target styles respectively.

The overall loss is the sum of the autoencoder and the style classifier losses.

The architecture diagram is shown below:

Image credit: Li et al. Domain Adaptive Text Style Transfer

Transformers and Language Models

The explosive progress in NLP over the last two years can be attributed to pre-trained language models that have been trained on massive unlabeled data. Naturally, one might be curious about how these language models can be leveraged to improve upon the style transfer task. Sudhakar et al. extend the Delete, Retrieve, and Generate framework explained earlier in this post. They utilize a transformer for the Delete step to determine the style-specific words to be deleted. The Generate step uses a powerful language model based on Open AI’s GPT-2 to generate sentences.

What is in store for the future?

Much of the pitfalls mentioned earlier still apply today. This field has seen many false dawns with adversarial methods, variational autoencoders being touted as game-changers but ultimately falling short. Future research will likely be focused on exploring more creative ways to leverage external large-scale data, be in the form of language models or in training set augmentation.

Datasets

If you would like to play around or conduct research on this task, here are some good datasets to get started with.

Yahoo GYAFC dataset for formality transfer

Shakespeare dataset for text modernization

Bible dataset for text simplification and text archaification