Highlights from the 2nd Workshop on Abusive Language Online

25 Jul 2019The ALW2: 2nd Conference on Abusive Language Online workshop at EMNLP was conducted on October 31, 2018. There were a total of 21 papers accepted at this workshop, and this post will try to summarize the nuggets of information and insight from those papers that I found most interesting.

Problem Definition

I am writing this post right on the heels of the mail bomb and synagogue shooting terror attacks in the U.S. In both cases, it was later determined that the perpetrators were involved in online abuse on mainstream social networks. There is growing pressure on governments (hard-hitting GDPR style regulation incoming?) and social media behemoths to deal with this problem. While optimists in the tech industry have already hailed machine learning as the messiah that would be a panacea for online abuse and all its manifestations (hate speech, offensive speech, cyberbullying etc), the complexity of this problem goes way beyond its technical aspects, including issues with determining what constitutes abusive speech in the first place and what steps should be taken once it is detected. This is effectively a cat-and-mouse game, with offenders coming up with neologisms, structural obfuscations, euphemisms, and dog whistles in order to evade automated abusive speech filters.

A production ML system would have the unenviable task of trying to maintain the precarious balance between false positives (which can be seen as an attack on free speech) and false negatives (which can be seen as being unresponsive to abuse victims). Given current limitations of state-of-the-art NLP systems in common sense reasoning and the ability to effectively incorporate world knowledge, how effectively can our models combat abusive language? Let us find out.

Nuances

Singh et al., point out that abuse and aggression are correlated concepts but they do not entail one another. For example, banter and jocular mockery are abusive constructions but they are not of an aggressive nature.

Magu et al., work on the interesting problem of finding code words or euphemisms that are used in place of swear words or other offensive terms that can be picked up easily by a hate speech filter.

To guide their discovery, they make some key assumptions about the structure of euphemistic words:

-

The words are nouns, and they directly replace the offensive word in a sentence without affecting the sentence structure, so a part-of-speech tagger would still label them correctly.

-

The words used do not have a negative connotation already (if they did, they would be already classified as hate speech, thus defeating the purpose)

-

They are neither overly general (words like ‘somebody’ etc) nor overly specific(proper names etc)

One method by which they find code words is to find how different the word embeddings are when trained on a corpus that is semantically neutral and one that contains hate speech. By using cosine similarity, words whose embeddings are further apart are judged to be candidates for code words. Other methods, including ones that exploit eigenvector centralities, are detailed in their paper.

Models

Several papers show results that suggest a consensus that character based models, be it character n-grams or character based embeddings are more effective than their word based counterparts. This is because character based models can uncover structural obfuscations of abusive words that are used to evade filters (e.g., a55h0le,n1gg3r). These obfuscations can be complicated enough that simple spelling correction algorithms like edit distance are unable to detect them. Moreover, certain character sequences are more likely to be involved in abusive constructions than others.

Mishra et al., experiment with several methods, the gist of which is below:

The input consists of the sequence of words in a text w1,w2,…wn. The words are represented by d-dimensional embeddings, initialized with GLoVe vectors. OOV(Out-of-Vocabulary) words for whom GLoVe vectors are not available are each initialized to a different random value. The embeddings are fine-tuned during the training process. The input is fed to a 2-layer GRU(Gated Recurrent Unit) with an output softmax layer that determines whether the input contains hate speech and also the type of hate speech (racism, sexism etc)

The authors also show that concatenating the last hidden state of the GRU with L2-normalized character n-gram counts results in improved metrics.

Fine tuning word embeddings during training can thus accommodate OOV words in the training set to some extent. What about OOV words in the test set? Inspired by MIMICK-RNN from Pinter et al., , the authors propose a ‘character-based word composition model’ to generate embeddings for OOV words in the test set. The training is done as follows: The input consists of characters represented by 1-hot vectors which are passed through a 2 layer BiLSTM and outputs a d-dimensional embedding for the word composed of the concatenation of these characters. The loss function is simply the mean squared error between the generated embedding and the task-tuned word embeddings from the training set! This is done to endow the generated embedding with characteristics from both the GLoVe construction and the fine-tuning.

The generated embeddings using the above process do not take into account the surrounding text context for each word, thus causing issues with word sense disambiguation. To dispel this, the authors propose using context-aware representations for characters instead of 1-hot vectors in the training process mentioned above. The context-aware representations are generated using an encoder architecture. For an input sequence of words, the encoder takes as input the sequence of characters that make up the words represented by 1-hot vectors, including the space character. The input is passed through a biLSTM which produces hidden states h1,h2,…hn for each character. The hidden states are then taken as the context-aware representations for each character. The training process then proceeds as mentioned above.

The authors report that using a 1-layer CNN with global max pooling in place of the 2 layer LSTM resulted in savings in training time while giving comparable results. This trend of preferring CNN based architectures for performance reasons is seen in other papers at this workshop too. For example, Svec et al., observe that using RCNNs instead of LSTM resulted in lesser training time with no cost to accuracy. They also note that their RCNN architecture used 8.5 times less parameters than their LSTM architecture to obtain comparable results.

Other models that showed improvements on metrics include Latent Topic Clustering, using Doc2Vec representations, and training set augmentation and generation using ConceptNet and Wikidata.

Hand-coded features

Singh et al., experiment with feature engineering and use features such as the count of abusive words in the input, number of tokens, presence of URL’s, phone numbers, hashtags, and number of upper-cased words. They show that an SVM that takes these input features is competitive with LSTMs.

Unsvag et al., experiment with user-related features like gender, network features, user profile information, and user activity information. They conclude that user-related features are of little to no benefit. Network features were found to be slightly useful, but it was dependent on the dataset (and subsequently, the social network being used).

Domain Adaptation.

To account for differences in the training and test set distributions, Gunasekara et al., show improved results by using semi-supervised learning using pseudo-labeling. In this method, the test set is split into n-folds. The training set and n-1 folds of the test set are trained, with the test set labeled by ‘pseudo-labels’, which are the predictions calculated by the classifier during the training process. The resulting classifier is evaluated on the test set and the process is repeated for all folds. They mention that this method is equivalent to entropy regularization (which I don’t understand well enough to talk about).

To tackle domain adaptation Karan et al., find success with the Frustratingly Easy Domain Adaptation technique.

Interpretability

Model interpretability seems to be a key requirement for systems that are to be placed in production, as companies/speech moderators might be required to justify why exactly a particular comment or post has been flagged as inappropriate.

Svec et al., propose a two step process for classifying abusive speech while providing interpretability of the classification decision. The first step is a RCNN based classifier that classifies input text as being inappropriate or not. The second step is used to identify the ‘rationale’ for classifying text as inappropriate. This is done by selecting a subset of the text that contributes most to the classification decision.

The rationale is generated by a model consisting of two components — the generator and the classifier.

At its output layer, the generator generates probabilities for each word in the input that determine whether they are selected as part of the rationale or not.

The classifier then uses only the words selected as the rationale by the generator to determine if the text is inappropriate or not.

The two models co-operate — the output of the classifier provides feedback on the quality of the generated rationale. This is because if the rationale was right, the classifier would make the right decision and vice versa.

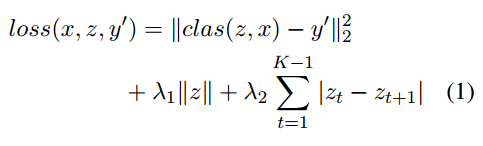

The authors propose two restrictions on the form of the rationale: the rationale should consist of only a few words, and those words should be present close to each other. This is achieved by using a rather elegant regularization objective -

z is a list of binary flags that states whether each word in input x has been selected as the rationale. The two hyperparameters can be used to control the number of words selected as the rationale and also forces the selected words to be in a row.

It is to be noted that selecting the words in the rationale plays no part in improving the original classification task of classifying comments as inappropriate or not. That task is already completed in the first step as mentioned above. The only purpose of the rationale is to provide interpretability to the model.

Cindy Wang experiments with three different methods to provide interpretability into her CNN-GRU model for classifying hate speech.

The input to the CNN-GRU model is a sequence of word embeddings representing the input words. This is fed to a 1-D convolution and max pool layer whose output is then fed to a GRU layer. The GRU output is passed through a max pooling layer which is then passed to the output softmax layer that makes the final predictions.

For this model, three different methods were used to gain insight into the model’s inner working:

-

Partial Occlusion: The author takes inspiration from partial occlusion used in image classification tasks and applies it to the textual domain. Each input token is iteratively replaced with the

token and the classifier is run on it. The resulting classifier probabilities are visualized using a heatmap. The heatmap shows the words that have the most effect on the classifier output. Using this method, the author was able to spot overlocalization (where the classifier is overly sensitive to certain unigrams or bigrams) and underlocalization( where the classifier is not sensitive to any region of the input), which cause misclassification. The author also found out that certain sensitive regions crossed sentence boundaries, thus causing misclassification. This information could then be used to modify the architecture and make the classifier more robust. -

Maximal Activations: For each unit in the final global max pooling layer of the model, its activations are calculated over all inputs and the top scoring inputs are selected. The author concludes that their model learns some lexical and syntactic features but fail to detect fine-grained semantics.

-

Synthetic text examples: This method is used to find the individual words that are determined by the model as being indicative of hate speech. For each word in the corpus, a sentence of the form ‘They call you

’ is fed to the model as input. The author found that for the corpus that they were experimenting with, the model along with swear words, also determined some semantically neutral words from dialect-specific terms and vernaculars as being offensive.

Datasets

Some papers introduced new hate speech datasets for research. de Gilbert et al., have released a dataset consisting of posts extracted from the white supremacist website Stormfront, labeling them as containing hate speech or not, with an inter-annotator agreement of around 90 percent. (Doesn’t the act of posting on Stormfront in itself constitute hate speech? haha) Sprugnoli et al., have released a dataset for cyberbullying, constructed by role-playing students and researchers. They acknowledge and discuss the ethical and epistemic issues involved in preparing such a dataset, including the observer effect. Ljubesic et al., release two datasets of news comments from Slovene and Croatian media that includes deleted comments.

Conclusion

This problem domain is only going to gain more prominence in the foreseeable future. Challenges abound in the domain, including the labeling of what constitutes abusive speech. Just as an example, in one of the papers there were some example comments that the authors mentioned were examples of speech that are fine, which I disagreed with. On the technical side, our current models still seem to be heavily reliant on lexical and syntactic features for making decisions. I am currently trying to reproduce some of the papers and will be uploading some stuff to Github soon. I will try to make a follow-up post with some more insight.

The next post will be about papers in EMNLP related to semantics. I hope people find this post useful!